|

Research Article

Heritage across horizons: Role of socializing entities in nurturing African ethnic identity

1 Department of Psychology, University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria

2 School of Psychology, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

Address correspondence to:

Omonigho Simon Umukoro

Department of Psychology, University of Lagos, Lagos,

Nigeria

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 100017P13OU2024

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Umukoro OS, Baguma PK. Heritage across horizons: Role of socializing entities in nurturing African ethnic identity. Edorium J Psychol 2024;7(2):1–13.ABSTRACT

Aims: Emigration by Africans raises important questions about the preservation of cultural heritage and ethnic identity among African diaspora. This study examines the role of familial socialization and social resilience in shaping the ethnic identities of African adolescents born abroad.

Methods: The study adopted a cross-sectional survey design in which data were obtained via an online survey among Nigerian students born and raised in the United Kingdom by Nigerian migrant families. Data from a sample of 212 college students were obtained via Google forms. Snowballing techniques were adopted in reaching eligible participants for the study. A structured questionnaire for data collection was constructed using standardized scales that measured each of the study variables.

Results: Results obtained suggest that both covert and overt dimensions of familial socialization have a statistically significant predictive relationship with ethnic identity [F(2, 209) = 3.842; p<0.05], with the covert dimension having a slightly stronger predictive strength (β = 0.212; p<0.05) compared to overt dimension (β = 0.203; p<0.05). Furthermore social resilience emerged as a significant moderator in the relationship between familial socialization and ethnic identity (ΔR2 of 4.2%).

Conclusion: These findings underline the importance of both familial and community support in nurturing and preserving ethnic identities within diaspora communities. Recommendations were made toward the production of an “African Heritage Kit,” tailored to teach and recommend familial socialization practices for preserving African cultural heritage across generations.

Keywords: African migrants, Ethnic identity, Familial socialization, Nigeria, Social resilience

INTRODUCTION

The phenomenon of emigration, often colloquially referred to as “Japa” in Nigeria, has taken root as a defining feature of the modern African experience [1]. While the reasons for this mass exodus are complex and multifaceted, it can be traced back to the turbulent decades of the 1970s and 1980s when Nigeria faced political instability, military interregnums, and a volatile economy [2]. During these years, a significant number of young Nigerians embarked on journeys to the Western world, primarily the United States and the United Kingdom, in pursuit of a more secure and prosperous future. Some ventured further afield, even as far as Ukraine. Over time, this wave of emigration has swelled, with more and more Nigerians leaving their homeland to chase their dreams abroad. The presence of a significant Nigerian diaspora in every part of the world is a testament to the resilience, ambition, and adaptability of the Nigerian people [3]. Many members of this diaspora have achieved distinction in various fields, becoming leaders in education, science, technology, business, and more. They also serve as a crucial financial lifeline to their home country, with reports indicating that they remit approximately $25 billion annually. This financial support plays a significant role in Nigeria’s economy and contributes to the well-being of countless families and communities.

However, beneath the surface of this outwardly positive narrative, there exist a host of challenges that have been documented in various studies. These challenges highlight the multifaceted consequences of the “Japa” movement on both the individuals who leave and the societies they leave behind. One of the most poignant and concerning issues which has received little attention is the gradual erosion of African identities, particularly among the generations of children born to African emigrants who have settled in Western countries [4]. This process of identity erosion raises important questions about the preservation of cultural heritage and the long-term impact of emigration on African ethnic identities. As a result of this mass movement, questions about cultural assimilation, integration, and the preservation of African heritage have become increasingly relevant [5],[6]. The evolving African identity is not only a matter of personal and familial concern but also holds broader implications for African nations and their global standing. Ethnic identity is a multifaceted construct that is deeply rooted in cultural traditions, languages, beliefs, and customs. Within the context of this discourse, ethnic identity is defined as feelings of belonging to a particular ethnic group [7]. As the African diaspora continues to expand, it becomes increasingly relevant to explore how these elements of identity are preserved, adapted, or sometimes lost.

One of the central focuses of this study is to examine the role of familial socialization in shaping the ethnic identities of African adolescents born abroad. Families play a crucial role in transmitting cultural values and traditions to the next generation [7]. However, the challenges and opportunities presented by life in a foreign country can exert considerable influence on how these values are transmitted and embraced. The study also focuses on the concept of social resilience which is integral to understanding the ways in which ethnic identities are sustained among this cohort of African adolescents. Social resilience refers to an individual’s belief in an in-group’s capacity to support and recovery resources during challenging times. It highlights some form of community support received by an individual in adapting to change and adversity while preserving cultural and social bonds. In the context of African identity erosion, it encompasses the strategies and support systems that communities employ to help its members resist the pressures of assimilation and cultural dilution. By understanding the dynamics of these constructs, insights of the preservation-erosion continuum of African ethnic identities within the global diaspora would be unearthed.

Theoretical foundations

Bronfenbrenner’s [8] ecological systems theory provides a holistic framework upon which this study is hinged. The theory suggests that a child’s development is affected by the different environments that they encounter during their life, including biological, interpersonal, societal, and cultural factors. Within the immediate family environment, known as the microsystem, familial socialization plays a crucial role. Moving to the mesosystem, interactions between the family and other microsystems like schools and peer groups are essential. These external influences can either support or conflict with the family’s messages, affecting how an adolescent perceives their ethnic identity. The exosystem introduces the concept of social resilience, serving as an indirect influence. The macrosystem encapsulates the broader cultural, societal, and ideological context. This includes the dominant culture’s attitudes toward diversity, multiculturalism, and the traditions of the African diaspora. The interplay between these macro-level factors shapes an adolescent’s ethnic identity. Lastly, the chronosystem accounts for changes over time. Shifting societal attitudes, immigration policies, and global events can all impact how these adolescents understand and express their ethnic identity.

Tajfel’s [9] Social identity theory (SIT) is also a relevant theory which explores how individuals categorize themselves and others into social groups, leading to the formation of social identity. When applied within the context of migrant Africans and the preservation of their ethnic identity, the theory provides a valuable framework for understanding the dynamics at play. For instance, SIT suggests that individuals categorize themselves and others based on shared characteristics, creating in-groups and out-groups. In the context of African emigration, this categorization may be observed in the formation of diaspora communities, where individuals identify with their shared African heritage while interacting with other cultural groups in their new environment. Belonging and obtaining support from such indigenous groups while living in Western societies may facilitate and buffer individual efforts by Africans to identify with their ethnicity and cultural values. The theory further posits that people tend to compare their in-group favorably to out-groups; such that African immigrants who consciously identify with their ethnicity may adopt rationalized comparisons to highlight the positives of their cultural heritage and identity over the dominant culture of their new host country. This process can influence how they perceive and preserve their ethnic identity [10].

Literature Review

Familial socialization and ethnic identity

Familial socialization encompasses the rich tapestry of experiences and influences that families provide to their members. From an early age, children are immersed in the cultural heritage of their ethnic background through interactions with parents, grandparents, and extended family members [11]. Within the family unit, they learn the language, customs, rituals, and practices that are intrinsic to their cultural identity. Values and beliefs, deeply intertwined with the cultural heritage, are also imparted within the family environment [12]. Parents and caregivers instill cultural values, moral principles, and religious beliefs that have been passed down through generations. These teachings help individuals develop a sense of right and wrong, shaping their decision-making processes and behaviors in alignment with their ethnic identity [13]. Language is also a cornerstone of familial socialization, serving as a key element of cultural preservation. Families who communicate primarily in their native language at home contribute significantly to the continuation of that language within younger generations. The ability to speak, understand, and write in one’s ethnic language is not only a linguistic skill but also a testament to one’s connection to their cultural roots [14]. Cultural practices and celebrations, often observed within the family, play a crucial role in maintaining and nurturing ethnic identity. Families partake in festivals, traditions, and rituals that are unique to their ethnic group [15] . These events serve as a living link to the past, allowing children to learn about their heritage and develop a sense of belonging within their cultural community.

Beyond the transmission of cultural elements, familial socialization is instrumental in identity development. The way parents and extended family members convey their cultural identity has a profound influence on how individuals perceive themselves and their place within their ethnic group [16]. This process of identity formation is deeply interwoven with familial interactions and the messages conveyed within the family unit. However, familial socialization faces unique challenges within diaspora communities. Exposure to the host culture and the need for adaptation can sometimes create tension. Families must navigate a delicate balance between preserving their ethnic identity and integrating into the host culture, a process that is highly individualized and can vary significantly between families [7].

Generational differences further complicate the dynamics of familial socialization. Second- and third-generation individuals may experience disparities in how their families transmit culture compared to first-generation immigrants. This generational gap can give rise to distinctive challenges in maintaining and strengthening ethnic identities [17]. The impact of familial socialization on the well-being of individuals within diaspora communities is substantial. A strong connection to one’s cultural identity instilled through family interactions can provide a profound sense of pride and belonging. Conversely, the erosion of ethnic identity within the family unit may lead to feelings of cultural disconnection and identity crisis [18]. Over the years, several scholars [19],[20],[21],[22],[23],[24],[25] have focused on understanding this intricate relationship.

Using a Web-based survey, Mohanty et al. [19] examined the relationship between parental support for cultural socialization and its effect on self-esteem of 82 adult international adoptees. Feelings of belongingness and ethnic identity were predicted to serve as mediators between the central variables. The results showed a positive relationship between cultural socialization and self-esteem, which was mediated by a feeling of belongingness and one aspect of ethnic identification (marginality) among Asian born international adoptees. These data suggest that counselors should raise awareness and knowledge of adoptive parents about the importance of cultural continuity in the child’s upbringing. Similarly, Umana-Taylor et al. [20] examined the longitudinal associations between family ethnic socialization and youths’ ethnic identity among a sample of Mexican-origin youth. Findings from multiple-group cross lagged panel models over a 2-year period indicated that for U.S.-born youth with immigrant parents, the process appeared to be family driven: Youths’ perceptions of family ethnic socialization in late adolescence were associated with significantly greater ethnic identity exploration and resolution in emerging adulthood, while youths’ ethnic identity during late adolescence did not significantly predict youths’ future perceptions of family ethnic socialization. Conversely, for U.S.-born youth with U.S.-born parents, youths’ ethnic identity significantly predicted their future perceptions of family ethnic socialization but perceptions of family ethnic socialization did not predict future levels of youths’ ethnic identity, suggesting a youth-driven process.

In more recent times Truong et al. [21] explored differences and similarities in ethnic identity, familial ethnic socialization and, parental ethnic socialization between ethnic majority, minority, and multiracial groups. Their findings showed that ethnic majorities experienced significantly lower ethnic identity than either ethnic minorities or multiracial groups, which was consistent with prior research [17]. Further outcomes showed that ethnic majorities scored lower of familial socialization compared to ethnic minorities and multiracial groups. In addition, Tram et al. [22] examined the relationship between ethnic identity, family ethnic socialization, heritage language ability, and desire to learn a heritage language in a sample of 91 U.S. psychology graduate students.

Adopting qualitative approaches, Jones and Rogers [23] invoked a critical macro and micro perspective to fully consider how parents influence necessarily intertwines with macrosystem dynamics of anti-Blackness, white supremacy, and monoracism for multiracial Black youth’s identity meaning-making in the context of Black Lives Matter. They found that young adults mention parents or familial adults when discussing their racial identity to recount parental guidance on racial identity, illustrate the racial politics of multiracial identification, and expose the dynamics in navigating shared and unshared identity spaces within the family; these highlight the relevance of parental socialization in the adulthood years.

Social resilience and ethnic identity

The interplay between social resilience and ethnic identity is a complex and fascinating subject that underscores the dynamic nature of cultural preservation, particularly within diaspora communities. It delves into how individuals and their communities adapt, persevere, and sometimes evolve in response to the challenges of retaining their ethnic identity in the face of external influences. Social resilience, in this context, refers to an individual’s belongingness and belief in a community with the capacity to support resilience of its members in preserving their cultural and ethnic heritage [26]. It encapsulates the strategies and support systems that individuals, their families, and their communities employ to resist the pressures of assimilation and cultural dilution. It is an essential aspect of understanding how ethnic identities endure and evolve. Communities within the diaspora often create social networks and organizations that serve as pillars of support for the preservation of their ethnic identity [27]. These networks foster a sense of belonging and provide individuals with opportunities to engage in cultural activities, connect with like-minded individuals, and celebrate their heritage. They therefore serve as hubs for maintaining cultural practices, passing down traditions, and reinforcing a sense of ethnic belonging [28].

Social resilience is not only about maintaining the status quo but also about adapting and evolving. It involves the ability to integrate aspects of the host culture while retaining the core elements of one’s ethnic identity [29]. Successful social resilience allows individuals to embrace diversity, bridge cultural gaps, and engage in cross-cultural exchanges while still preserving their unique cultural roots. Challenges, however, are inherent in the process of social resilience. The pressure to assimilate into the host culture can be strong, and individuals and communities must navigate the delicate balance between adaptation and preservation. This balancing act can vary among individuals and communities, leading to diverse experiences and outcomes [30]. Understanding the dynamics between social resilience and ethnic identity is crucial for the well-being and cohesion of diaspora communities. It highlights the strategies and resources that can be employed to nurture and protect cultural identities while also acknowledging the necessity of adaptation and change. By exploring the multifaceted relationship between these two aspects, one gains valuable insights into the preservation and evolution of ethnic identities in a globalized world, where the forces of cultural integration and diversity continually shape the experiences of diaspora communities as evidenced by previous studies.

For instance, Zheng [31] examined the link between ethnic identity and resiliency in White people and ethnic minorities (including Black and Indigenous People of Color). Participants were recruited through the SONA system and instructed to complete two questionnaires. Results showed that White group did not have as strong of an ethnic identity when compared to those in the ethnic minority group. Further correlational analyses showed that ethnic identity and resiliency were highly correlated among the ethnic minority group, while there was no significant correlation between the two variables among the White people. Similarly, in contextualizing immigrant and refugee resilience, Güngör and Strohmeier [32] suggested that the provision of opportunities for immigrants to express their ethnic identity and have it recognized within the community can help these groups to build resilience, which is a key factor in immigrant well-being and a non-detrimental process of acculturation. Berding-Barwick and McAreavey [33] highlighted how immigrants proactively make strategic choices and assume responsibility to preserve their identities—even if that depends on changing underlying structural issues. They showed that, despite a hostile immigration environment, as found in the United Kingdom, immigrants were able to utilize their resilient nature in adapting to their environment.

Conceptual framework and hypotheses

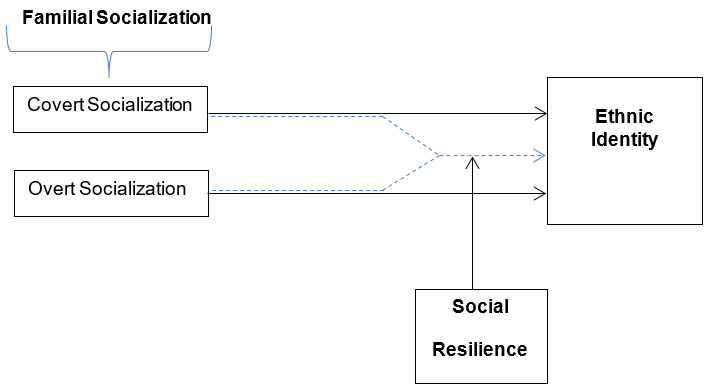

Based on the review of literature, it is logically expected that dimensions of familial socialization should have an influence on the extent of to which African adolescents born and raised in Western climes can identify with their African ethnicities. Furthermore, their level of social resilience may have a moderating role to play in the link between familial socialization and ethnic identity. Therefore the empiricism of the conceptual framework provided below would be tested via the hypotheses formulated thereafter.

As depicted by the framework in Figure 1, the following hypotheses are formulated for testing using appropriate statistics

Hi: Dimensions of familial socialization will have significant joint and independent influence on ethnic identity of African adolescents in Western climes.

Hi: Social resilience will significantly moderate the relationship between familial socialization and ethnic identity of African adolescents in Western climes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design and population

The study adopted a cross-sectional survey design in which data were obtained via an online survey among Nigerian students born and raised in the United Kingdom by Nigerian migrant families. Data from a sample of 212 college students were obtained via Google forms. Snowballing techniques were adopted in reaching eligible participants for the study. The distribution of participants showed that 57% were female while 43% were male. Their ages ranged from 18 to 25 years with a mean age of 22.4 years and a standard deviation of 2.1. In terms of the African heritage, majority (47%) of the participants were from Yoruba ethnicities, 34% were from Igbo related tribes while 19% were from Hausa related ethnicities.

Measures

A structured questionnaire for data collection was constructed using standardized scales that measured each of the study variables. In order to achieve standardization of the scales for the population of interest, a pilot study was conducted among a cohort of students in a selected Federal University in Nigeria. Based on the outcomes of the item analysis, items in each scale that did not meet an acceptable reliability estimate were reworded to achieve cultural relevance. The Cronbach alphas of the adapted scales are reported in the scale descriptions below.

Section A of the questionnaire was designed to capture the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents. The items in this section highlighted variables of age, sex, and ethnic affiliation. Age was measured on a ratio scale with respondents expected to insert their actual age as a number in years. Sex was measured on a dichotomized nominal scale as male or female. Ethnic affiliation was measured as a nominal variable and categorized into three major traditional ethnic groups in Nigeria based on regional location.

Section B of the questionnaire comprised items from the Ethnic Identity Scale [34]. The scale assesses feelings of belonging to a particular ethnic group, measured across three dimensions; exploration, resolution, and affirmation using 7, 4, and 6 items respectively. Sample items for each dimension include I have participated in activities that have exposed me to my ethnicity (exploration), My feelings about my ethnicity are mostly negative (affirmation), and I am clear about what my ethnicity means to me (resolution). The scale comprises of both positively and negatively worded items. Response to the items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale which ranges from “1=Does not describe me at all” to “4=Describes me very well.” According to the original authors, the subscales have moderate strong coefficient alphas ranging from 0.84 to 0.89 across diverse ethnic samples of adolescents [34]. In this study a Cronbach alpha of 0.81 was obtained for the composite scale.

Section C of the questionnaire was made up of items from the familial ethnic socialization measure [35] which measures the degree to which participants perceive that their families socialize them with respect to their ethnicity. The scale has items measuring covert (7 items) and overt (5 items) dimensions of familial ethnic socialization with respective sample items such as Our home is decorated with things that reflect my ethnic background and My family talks about how important it is to know about my ethnicity. These items are responded to on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “1=not at all” to “5=very much” with high scores indicating higher perception of familial ethnic socialization and low score indicating lower perceptions of familial ethnic socialization. The original author of the scale obtained alpha coefficients ranging from 0.92 to 0.94 with ethnically diverse samples [35]. In this study, the researcher obtained a Cronbach alpha of 0.84.

Section D of the questionnaire measured social resilience in form of an individual’s belongingness and belief in an ethnic community with the capacity to facilitate resilience of its members. This was measured using the Transcultural Community Resilience Scale (T-CRS) developed by Cénat et al. [36]. The scale contains 28 items for respondents to indicate their level of agreement with each one, using a Likert scale ranging from “1=strongly disagree” to “5=strongly agree.” Factor analysis as obtained by the original authors highlights three dimensions of community resilience within the scale which include; community strength and support (14 items), community trust and faith (5 items), and community values (9 items). Respectively, sample items from each dimension include When I go through hard times, there are people in my ethnic community I can talk with, I have trust in the social services of my community, and In my community, there are important traditions of mutual support. The 28-item structure of the Transcultural Community Resilience Scale showed excellent internal consistency with a Cronbach Alpha of 0.96. Among this study’s population, a Cronbach alpha of 0.79 was obtained.

Procedure

The researcher had access to a contact person (a Nigerian migrant) in the United Kingdom whose assistance was needed to facilitate the data collection process. The contact person was to identify online platforms (e.g., WhatsApp Groups) in colleges and universities in the United Kingdom hosting Nigerian students and provide the survey link for eligible participants. The survey link was accompanied with the eligibility criteria (i.e., Nigerian students born and raised in the United Kingdom by Nigerian migrant families) for potential study participants. Upon clicking the survey link, participants were directed to an information page where relevant details and ethical considerations about the study were provided. Participants who gave their consent to participate in the study were directed to the instrument items; those who declined to participate in the study were directed to the submission page of the instrument. A clause was also inserted in the participant information page, prompting participants to share the survey link with other acquaintances who were eligible for the study; this provided an avenue for introducing exponential snowballing techniques in obtaining the study sample.

All submitted forms were received and collated in form CSV files at the back end of the Google form. After data cleaning processes, a total of 212 participant responses were deemed adequate and downloaded. The CSV data were transferred to Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) application software for further data analysis. Both linear and moderated regression analyses were used as statistical techniques for the hypotheses testing [37].

Hypotheses testing

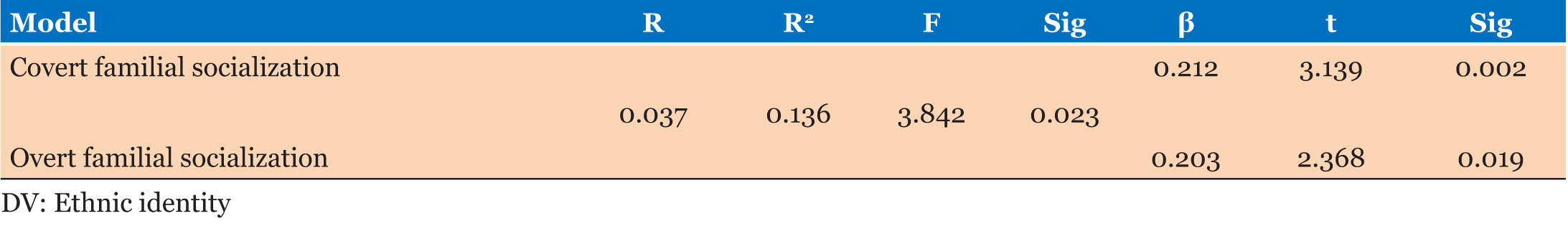

Hypothesis one stated that dimensions of familial socialization will have significant joint and independent influence on ethnic identity of African adolescents in Western climes. This hypothesis was tested using linear multiple regression analysis to identify the predictive roles of the independent variables in the model. A summary of the results obtained is presented in Table 1.

Results obtained from the table suggest that both covert and overt dimensions of familial socialization have a statistically significant predictive relationship with ethnic identity, as indicated by their p-values (Sig.). The beta values show that the covert dimension has a slightly stronger predictive strength (β=0.212; p<0.05) with ethnic identity compared to overt dimension (β=0.203;p<0.05). The R2 suggests that both dimensions have a significant joint contribution of about 13.6% in the variance of ethnic identity [F(2, 209)=3.842; p<0.05] among African adolescents in Western climes. The hypothesis stated is therefore supported.

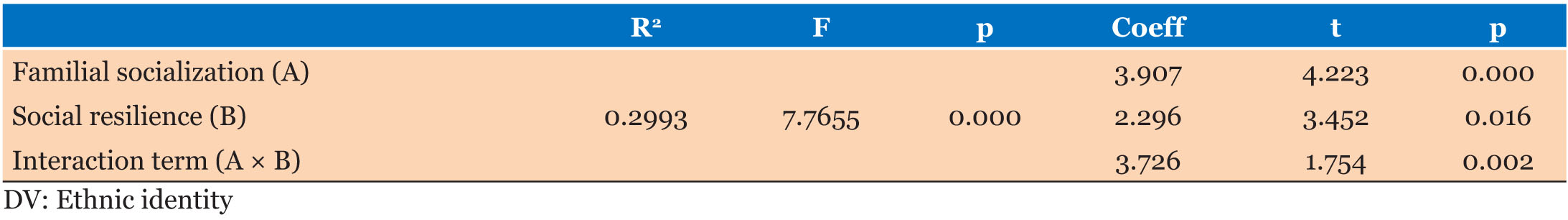

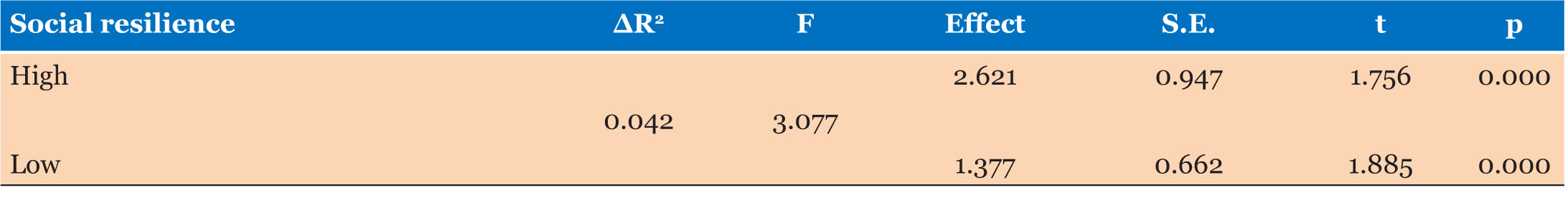

Hypothesis two stated that social resilience will significantly moderate the relationship between familial socialization and ethnic identity of African adolescents in Western climes. This hypothesis was tested using moderated multiple regressions to identify the direct and conditional effects of the moderator in the model. A summary of the results obtained are presented in Table 2.

Results from Table 2 show that both familial socialization and social resilience have statistically significant relationships with ethnic identity, as indicated by their p-values. Additionally, the interaction term (FamSoc × ScR) also has a statistically significant relationship with ethnic identity (β = 3.726; p<0.05). The significant interaction term suggests that the relationship between familial socialization and ethnic identity is moderated by social resilience. In other words, social resilience has a moderating effect on the relationship between familial socialization and ethnic identity in African adolescents in Western settings. The direction and conditional effects of the moderator in the model is presented in Table 3.

Table 3 provides information about the effects of social resilience at different levels (“High” and “Low”) on the dependent variable (ethnic identity), and it indicates that both levels of social resilience have a statistically significant impact on ethnic identity and produce a significant ΔR2 of 4.2%. The effect is however larger for the “High” level (2.621) compared to the “Low” level (1.377). The second hypothesis of the study is supported.

DISCUSSION

Findings from the first hypothesis provide emphasis that both covert and overt forms of familial socialization are important factors in influencing ethnic identity among African adolescents in Western settings. Serpell and Adamson-Holley [38] describe covert familial socialization as involving more subtle and indirect influences, such as cultural abstractions and non-verbal cues including celebrating ethnic holidays, playing songs specific to ethnic groups, attending ethnic festivals, decorating the home with items that reflect one’s ethnicity etc.; while overt familial socialization encompasses explicit and direct communication about cultural heritage, such as teachings about cultural background and histories, encouraging respect for the cultural values and beliefs of ethnic/cultural background, etc. As obtained from the study findings, both forms of socialization play a significant role in shaping ethnic identity, with covert dimensions providing a slightly stronger predictive influence. This suggests that a combination of implicit and explicit familial influences contributes to the development of ethnic identity in this context. Ntarangwi [39] suggests that an understanding these relationships is crucial for supporting and nurturing the ethnic identities of adolescents within diaspora communities.

The study’s findings are in line with prior research that highlights the importance of familial socialization in shaping ethnic identity. Harris [18] agrees that the strong connection to cultural identity instilled through familial socialization can provide a profound sense of pride and belonging. Conversely, the erosion of ethnic identity within the family unit may lead to feelings of cultural disconnection and identity crisis [18]. Additionally, the studies reviewed in the literature provide further insights into the relationships between familial socialization and ethnic identity. For instance, Mohanty et al. [19] found that parental support for cultural socialization had a positive impact on self-esteem among international adoptees, with ethnic identity mediating this relationship. Umana-Taylor et al. [20] examined the longitudinal associations between family ethnic socialization and youths’ ethnic identity among Mexican-origin youth, highlighting the importance of family-driven processes. Jones and Rogers [23] provide critical insights into how parent influence intertwines with macro-system dynamics in shaping multiracial Black youth’s identity, emphasizing the continued relevance of parental socialization in adulthood.

It is therefore the duty of parents, elders, and guardians within the African family to transmit cultural elements, including language, customs, rituals, and values [40]. This transmission is integral to the development of ethnic identity, as individuals learn and internalize their cultural heritage within the family setting [11]. The way parents and extended family members convey their cultural identity significantly influences how individuals perceive themselves and their place within their ethnic group. This process of identity formation is closely tied to familial interactions and messages within the family unit [16]. For African adolescents in Western settings, the balance between preserving their ethnic identity and integrating into the host culture can be challenging. Familial socialization in such diaspora communities must navigate this delicate balance, which can vary significantly between families [7].

The second hypothesis reveals that social resilience, the social resource to adapt, endure challenges, and maintain a positive self-concept, also has a statistically significant moderating impact on how familial socialization shapes ethnic identity. The findings imply that the availability and responsiveness of the broader African community within the diaspora is a significant factor that can sustain ethnic foundations laid through familial socialization. In other words, the efforts of the African family as a resource for sustaining ethnic identity is better achieved within a responsive African community in the diaspora. The moderating role of social resilience is further supported by Zheng [31] whose study suggests that the relationship between ethnic identity and resilience may be more pronounced in contexts where individuals face unique challenges related to their minority status.

Similarly, Güngör and Strohmeier [32] underscores how fostering ethnic identity within immigrant communities can be a critical factor in promoting resilience and well-being, which is consistent with the idea that social resilience moderates the relationship between familial socialization and ethnic identity. The use of resilience by immigrants, in Berding-Barwick and McAreavey’s [33] study, to preserve their identities aligns with the concept that social resilience can influence the relationship between familial socialization and ethnic identity. The ability to maintain ethnic identity despite challenges suggests the moderating role of social resilience.

CONCLUSION

This study provides some insight on how familial socialization, in its covert and overt forms, along with the moderating influence of social resilience, may influence the ethnic identity of African adolescents in Western settings. These findings underline the importance of both familial and community support in nurturing and preserving ethnic identities within diaspora communities, which can be a source of pride, belonging, and resilience for individuals navigating the complexities of cultural integration and identity development in their new environments. Overall, the study findings align with Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory by highlighting the critical role of the microsystem (family) and its connection to the macrosystem (community) in influencing the ethnic identity development of African adolescents in Western settings. Moreover, considering how these familial socialization practices may evolve over time (chronosystem) and interact with other systems (mesosystem) would provide a more comprehensive ecological perspective on ethnic identity development.

Limitations

The outcomes of this study are not without limitations. For instance, the external validity of the study outcomes may be limited by constraints associated with the use of an online survey tool for data collection which may not guarantee the participation and eligibility of the target audience, as well as, the representativeness of the sample. Moreover, issues of social desirability and biases in participant responses cannot be easily controlled for while using online surveys. Perhaps, the use of qualitative approaches in further replicated studies may provide more externally valid and robust findings. Furthermore, the outcomes of this study do not provide insight into the role of demographic differences and the confounding effect that their inclusion in the empirical model may have yielded. Irrespective of these limitations, the study findings are pivotal in gaining some understanding and plausible linkages between the selected socializing entities and ethnic identity among this cohort.

Recommendations

The process of migration and assimilation are threats to the sustenance of African ethnic identities among African migrants. It is the duty of Africans to ensure that their cultural heritage is not drowned by Western inventions and innovations. Therefore there is need for practical and proactive measures to be deployed by Africans to enrich and sustain their cultural heritage across generations, irrespective of time and space. It may be worthwhile for African entities in form of government and non-governmental agencies entrusted with preserving the African heritage to formulate and implement strategies that assist the African family to preserve its cultural heritage through processes of socialization. This can be achieved by introducing interventions in form of handy “African Heritage Kits” tailored to teach and recommend familial socialization practices for preserving African cultural heritage across generations. The kits should encompass a diverse range of elements, including language, traditions, customs, folklore, and values in multimedia formats. To initiate this endeavor, a dedicated task force could be formed, bringing together government representatives, nongovernmental organizations, cultural experts, educators, and community leaders to design the content of the African Heritage Kits.

Leveraging on digital technologies and resources of the African Research Universities Alliance (ARUA) Centre of Excellence in Notions of Identity, collaborative workshops and research projects can be launched to deepen the understanding of African identity dynamics in the development of the African Heritage Kits. These kits will integrate Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) interventions in promoting active learning and practical application of cultural preservation strategies. Mass production and strategic distribution of these kits will ensure accessibility at key points of departure for African migrants. Community engagement sessions and workshops will play a pivotal role in introducing and training individuals on the effective use of these kits within their families. A robust monitoring and evaluation system will gauge the impact of the initiative, with feedback mechanisms guiding continuous improvement. Advocacy for supportive policies and a sustainability plan will further fortify the initiative, ensuring the perpetual relevance and availability of the African Heritage Kits in the face of evolving challenges.

REFERENCES

1.

Okunade SK, Awosusi OE. The Japa syndrome and the migration of Nigerians to the United Kingdom: An empirical analysis. CMS 2023;11:27. [CrossRef]

2.

Premium Times. 2022. [Available at: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/opinion/551986-japa-by-toyin-falola.html]

3.

4.

5.

Contini P, Carrera L. Migrations and culture. Essential reflections on wandering human beings. Front Sociol 2022;7:1040558. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

6.

Gwerevende S, Mthomben ZM. Safeguarding intangible cultural heritage: Exploring the synergies in the transmission of indigenous languages, dance and music practices in Southern Africa. International Journal of Heritage Studies 2023;29(5):398–412. [CrossRef]

7.

Umaña-Taylor AJ, Hill NE. Ethnic–racial socialization in the family: A decade’s advance on precursors and outcomes. Journal of Marriage and Family 2020;82(1):244–71. [CrossRef]

8.

9.

Tajfel H. Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Social Science Information 1974;13(2):65–93. [CrossRef]

10.

11.

Morris AS, Ratliff EL, Cosgrove KT, Steinberg L. We know even more things: A decade review of parenting research. Journal of Research on Adolescence 2021;31(4):870–88. [CrossRef]

12.

Ruck MD, Hughes DL, Niwa EY. Through the looking glass: Ethnic racial socialization among children and adolescents. Journal of Social Issues 2021;77(4):943–63. [CrossRef]

13.

Huguley JP, Wang MT, Vasquez AC, Guo J. Parental ethnic-racial socialization practices and the construction of children of color’s ethnic-racial identity: A research synthesis and meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2019;145(5):437–58. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

14.

Rogers LO, Kiang L, White L, et al. Persistent concerns: Questions for research on ethnic-racial identity development. Res Hum Dev 2020;17(2–3):130–53. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

15.

Phinney JS. Ethnic identity exploration in emerging adulthood. In: Arnett JJ, Tanner JL, editors. Emerging Adults in America: Coming of Age in the 21st Century. American Psychological Association; 2006. p. 117–34. [CrossRef]

16.

Atkin AL, Yoo HC. Familial racial-ethnic socialization of multiracial American youth: A systematic review of the literature with MultiCrit. Developmental Review 2019;53:100869. [CrossRef]

17.

Franco M, Toomey T, DeBlaere C, Rice K. Identity incongruent discrimination, racial identity, and mental health for multiracial individuals. Counselling Psychology Quarterly 2019;34(1):87–108. [CrossRef]

18.

Harris JC. Multiracial college students’ experiences with multiracial microaggressions. Race Ethnicity and Education 2016;20(4):429–45. [CrossRef]

19.

Mohanty J, Keokse G, Sales E. Family cultural socialization, ethnic identity, and self-esteem: Web-based survey of international adult adoptees. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work 2007;15(3–4):153–72. [CrossRef]

20.

Umaña-Taylor AJ, Zeiders KH, Updegraff KA. Family ethnic socialization and ethnic identity: A family-driven, youth-driven, or reciprocal process? J Fam Psychol 2013;27(1):137–46. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

21.

Truong A, Tram JM, Wojda K, Anderson DM. Familial and parental ethnic socialization within majority, minority, and multiracial groups. The Family Journal 2021;29(1):95–101. [CrossRef]

22.

Tram JM, Huang A, Lopez JM. Beyond family ethnic socialization and heritage language ability: The relation between desire to learn heritage language and ethnic identity. The Family Journal 2023;31(4):562–71. [CrossRef]

23.

Jones CM, Rogers LO. Family racial/ethnic socialization through the lens of multiracial black identity: A M(ai)cro analysis of meaning-making. Race Soc Probl 2023;15(1):59–78. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

24.

Umukoro OS, Rowland-Aturu AM, Tomoloju OP, Wadi OE. Predictive role of personality on cyberloafing within the Nigerian civil service and the mediatory role of ethical climate. Edorium J Psychol 2019;5:100015P13OU2019. [CrossRef]

25.

Jones SCT, Anderson RE, Stevenson HC. Differentiating competency from content: Parental racial socialization profiles and their associated factors. Fam Process 2022;61(2):705–21. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

26.

Zaretsky L, Clark M. Me, Myself and Us? The relationship between ethnic identity and hope, resilience and family relationships among different ethnic groups. Journal of Education, Society and Behavioural Science 2019;32(2):1–14. [CrossRef]

27.

28.

29.

DeSimone JA, Harms PD, Vanhove AJ, Herian MN. Development and validation of the five-by-five resilience scale. Assessment 2017;24(6):778–97. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

30.

Lee RM, Robbins SB. The relationship between social connectedness and anxiety, self-esteem, and social identity. Journal of Counseling Psychology 1998;45(3):338–45. [CrossRef]

31.

Zheng M. Studying the Relationship Between Ethnic Identity and Resiliency: A Broad Approach. In BSU Honors Program Theses and Projects. Item 499. 2021. [Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/honors_proj/499]

32.

Güngör D, Strohmeier D. Contextualizing immigrant and refugee resilience: Cultural and acculturative perspectives. In: Güngör D, Strohmeier D, editors. Contextualizing Immigrant and Refugee Resilience. Advances in Immigrant Family Research. Cham: Springer; 2020. [CrossRef]

33.

Berding-Barwick R, McAreavey R. Resilience and identities: The role of past, present and future in the lives of forced migrants. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 2023:50(8):1843–61. [CrossRef]

34.

Umaña-Taylor AJ, Yazedjian A, Bámaca-Gómez M. Developing the ethnic identity scale using Eriksonian and social identity perspectives. Identity 2004;4(1):9–38. [CrossRef]

35.

Umaña-Taylor AJ, Fine MA. Methodological implications of grouping Latino adolescents into one collective ethnic group. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 2001;23(4):347–62. [CrossRef]

36.

Cénat JM, Dalexis RD, Derivois D, et al. The transcultural community resilience scale: Psychometric properties and multinational validity in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol 2021;12:713477. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

37.

38.

Serpell R, Adamson-Holley D. African socialization values and nonformal educational practices: Child development, parental beliefs, and educational innovation in Rural Zambia. In: Abebe T, Waters J, editors. Laboring and Learning. Geographies of Children and Young People. Volume 10. Singapore: Springer; 2017.

39.

40.

Akuma JM. Socio-cultural and family change in Africa: Implications for adolescent socialization in Kisii County, South Western, Kenya. The East African Review 2015;50:80–98. [CrossRef]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Author Contributions

Omonigho Simon Umukoro - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Peter Kakubeire Baguma - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guaranter of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the participants for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2024 Omonigho Simon Umukoro et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.